The outcome of the armed conflict in the former SFR Yugoslavia, between 1991 do 2001, is the violent death of 130 000 persons. Over 10 000 are still classified as missing. Serbia’s officials and institutions have, from the beginning of the armed conflict to this day, with very few exceptions, denied the involvement of the SFR and Serbian armed forces in the conflicts in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. They have also denied the existence of any war crimes on the territory of Serbia in relation to these armed conflicts.

As an antithesis to the practice of forgetting the atrocities of war, the platform ratusrbiji.rs strives to inform and educate about the existence of secret mass graves, concentration camps and torture, murders and persecution of minorities, forced mobilization, paramilitary units’ crimes, as well as the human rights breaches in the Presevo valley between 1991 to 2001. The platform does this through connecting court-determined facts, official data of state and international institutions, testimonies of witnesses, survivors and victims’ families, as well as public information gathered by civil society organizations in Serbia.

The platform ratusrbiji.rs was supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany. The content and opinions featured on the ratusrbiji.rs website are those of the Youth Initiative for Human Rights, and may not reflect the official stance of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany.

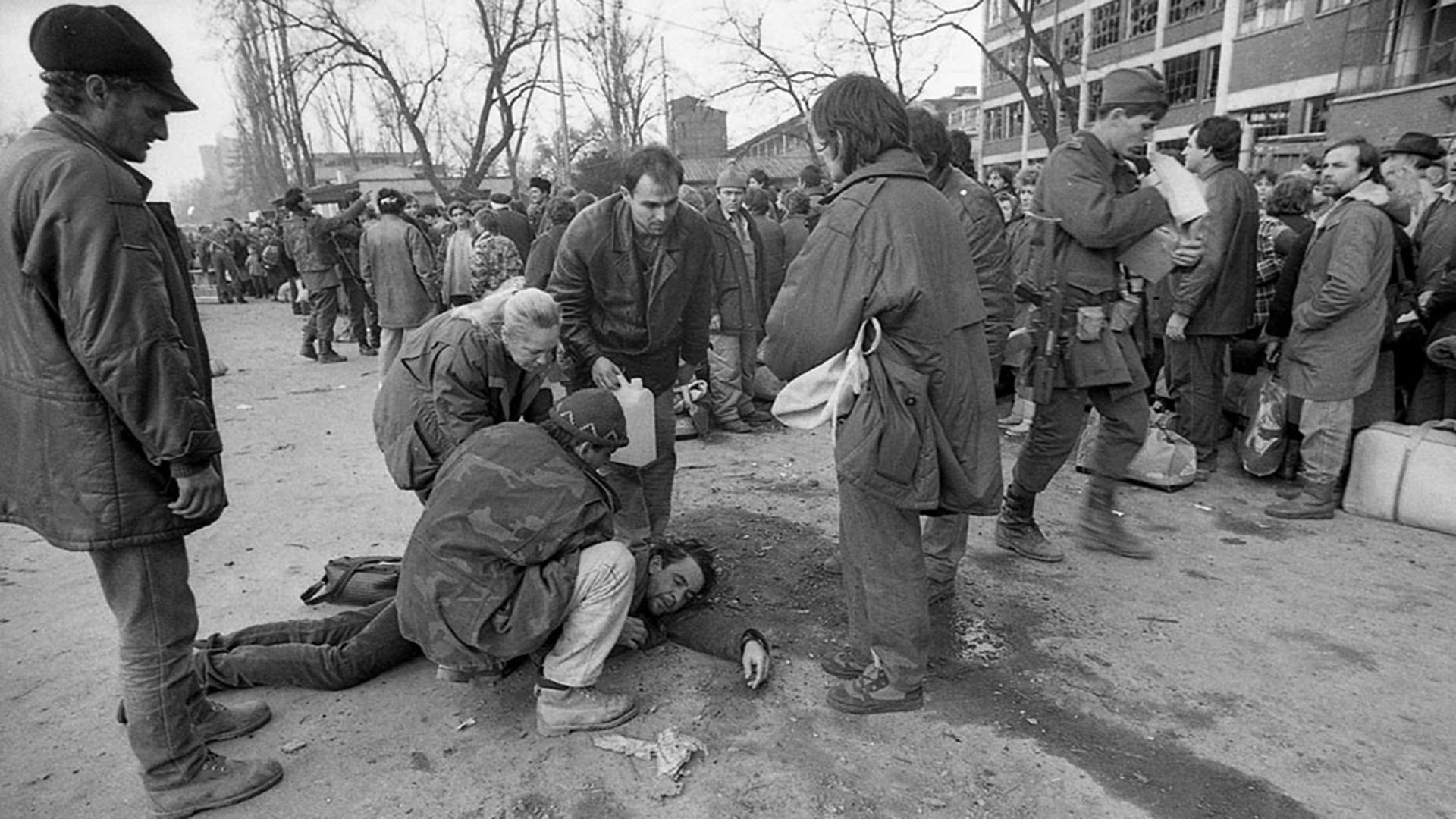

During 87 days, from August to November 1991, Vukovar (Croatia) was under siege of the Yugoslav People’s Army (JNA), the Territorial Defence and various Serbian paramilitary units. After the fall of the once wealthy and multi-ethnic town, many Croatian soldiers, as well as Croatian and Serbian civilians, women, children and the elderly, were brought to prison camps in Serbia. Balkan Investigative Reporting Network (BIRN) reports that, according to the Croatian Commission for the Missing and Imprisoned Persons, “a total of 7666 people were exchanged from all of the Yugoslav army-run camps from December 1991 until August 1992. Of that number, 219 were under 18, 932 were women and 424 were over 60. Almost half of the number were civilians, 46 per cent, while 52 per cent were combatants. The status of the other 4 per cent has not been established”.[footnote]Barbara Matejčić and Zoran Kosanović, “Revealed: Vukovar Croats Were Tortured in Niš”, BIRN, 27 January 2011 [/footnote]

Prison camps for Croats on the territory of Serbia were being opened as early as in October 1991. They were located on the compounds in Begejci and Stajićevo, in the Sremska Mitrovica Prison, the Penitentiary and Correctional Institution and Military Prison in Niš, the Military Investigative Prison (VIZ) and in the facilities of the Security Institute in Belgrade. A decision to open prison camps was signed by General Veljko Kadijević, at that time SFRY Federal Secretary for People’s Defence (Federal Defence Minister); the Legal Department and the Security Directorate of the Federal Secretariat for People’s Defence (SSNO) took part in preparing the decision. Technical and organisational details, that is, everything in relation to the operation of the camps, from food, through the selection of commanders and guards, to the decisions on releasing the prisoners was assigned to the JNA, that is, SSNO Security Directorate, which was intelligence and counter-intelligence section of the JNA.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]The guards at the camps were regular soldiers or members of the military police, while investigators mostly came from the JNA Security Directorate. The investigators were trying to force the prisoners into disclosing information or confessions about war crimes.

Upon arrival to the camp, the prisoners had to walk through the gauntlet, that is, to pass between a double row of soldiers who were punching and kicking them and beating them with sticks and other objects. Having walked through the gauntlet, the prisoners were forced to take off their clothes and hand over their personal belongings. Money and valuables were not returned to them when they left the camps. Inside the camps, the prisoners had to walk with their heads down and hands behind their backs, while the guards were beating them on a daily basis, even when they were going to the toilet, when they were forced to sing Chetnik songs. In addition to physical torture, the prisoners were exposed to psychological torture, as well. For example, the guards would take a prisoner to be executed, but instead of shooting them, they would burst into laughter. As a certain number of women were held at the camps, too, there were also the cases of rape. It was mostly cold at the camps, the prisoners were forced to sit and sleep on concrete, often without any covers, food was scarce, while personal hygiene and medical care were mostly denied.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]

The state of the camps was particularly difficult before the arrival of the International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC) in early December 1991, when the majority of murders and disappearances occurred.[footnote]Barbara Matejčić and Zoran Kosanović, “Revealed: Vukovar Croats Were Tortured in Niš”, BIRN, 27 January 2011[/footnote]

After ICRC’s arrival, conditions improved and the prisoners, having been registered, felt safer. Because of increased monitoring by the international community, the camps in Begejci and Stajićevo were soon closed down and the prisoners were transferred to the camps in Sremska Mitrovica and Niš.

On October 1 1991, a prison camp for Croats from Osijek, Vukovar, Vinkovci and surrounding places was founded in Begejci (today Torak). Until it was closed in December 1991, Begejci was a place of imprisonment for the members of Croatian military forces, as well as for a smaller number of reservists from Serbia who refused to participate in war and who were transferred to Begejci from Paragovo, a village near Novi Sad. Mostly Croats from Vojvodina and Croats arrested while passing through Vojvodina were held in Paragovo.

Other than them, some civilians, women and children were held in Begejci, too. It is estimated that around 750 persons[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]went through the camp, including 37 women.[footnote]Manda Patko, Fourth Forum for Transitional Justice in Pristhina, REKOM, 29 October 2008[/footnote]An article titled “Wild Guests of the Gentle Plains” published in the paper Zrenjanin in October 1991 brought a story of a collection centre in the Hunters’ House in Begejci, where members of the Croatian military forces were held, as well as civilians who were put there by the command of the JNA First Military Region. Đorđe Kitaresku, Secretary of the Fazan Hunters Club, testifies that the military police came to pick him before they fenced the camp area and that he had access to the camp and witnessed the violence. The camp in Begejci, i.e. an abandoned farmhouse, consisted of a building for prisoners and a building for soldiers; it was surrounded with barbed wire and illuminated by floodlights. The camp was secured by the police (SUP) with machine guns and dogs and its commander was JNA Lieutenant Colonel Nikola Petrović.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]The prisoners of the camp in Begejci were sleeping on concrete and using makeshift toilets. Food was scarce and there was only one bucket with water and one glass for all prisoners. The guards used to wake them up in the middle of the night and force to sing Chetnik songs.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016 [/footnote]

At the Goran Hadžić trial (Hadžić) before the International Criminal Tribunal for Former Yugoslavia (ICTY), doctor Mladen Lončar, a Croat from Ilok and a camp prisoner, testified to beatings and rapes that took place at the camp.[footnote]Mladen Lončar, testimony in the Hadžić trial before ICTY, 6 September 2013[/footnote]At the Vukovarska trojka trial (Mrkšić et al.), JNA Colonel Bogdan Vujić said that after four o’clock in the afternoon, the prisoners were left alone with the guards at the camp[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote], thus trying to minimise his responsibility for and awareness of the crimes committed.

The camp in Stajićevo was active from November 18 to December 22 1991, after which the prisoners were transferred to Sremska Mitrovica. Members of the Croatian military forces were held in Stajićevo, as well as civilians and a few medical doctors. The commander of the camp was Colonel Miroslav Živanović. The prisoners were interrogated by the members of JNA Security Directorate, the above-mentioned Colonel Bogdan Vujić was the interrogator, while General Aleksandar Vasiljević, Chief of the JNA Security Directorate, was visiting the camps. Aleksandar Vasiljević was the Deputy Chief of the JNA Security Directorate from 1990 to 1991 and then the Chief of JNA Security Directorate until 1992 when he went to early retirement. He was reactivated in April 1999 as a Deputy Chief of the Security Service of the Yugoslav Army, where he stayed until 2000. He retired in 2001.[footnote]Aleksandar Vasiljević was a prosecution witness in the cases of Slobodan Milošević and Goran Hadžić before ICTY, ICTY website [/footnote]

Since Stajićevo was an agricultural estate surrounded with high barbed wire, the prisoners were placed in stables, while the guards, military police officers, were always there. The prisoners were tied and only after the arrival of ICRC they were given access to the toilet, water and blankets. Although some of the prisoners were the elderly, sick, had gunshot wounds, could not move or were schizophrenic or diabetic, the army would not give them medicine, but told them that they would get it from the Red Cross.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]

On one occasion, three prisoners managed to escape, but the locals caught them, beat them up and called the army to pick them up.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016 [/footnote]According to the statement of Žarko Pavletić, prisoner in Stajićevo, Ivan Kamerla, Ivan Kunac, Branko Koh and Božo Kelava were killed at the camp.[footnote]Branka Mihajlović, “Hoće li Vukovarci postaviti spomen obeležje u Zrenjaninu”, Radio Slobodna Evropa, 5 October 2009[/footnote]

The Sremska Mitrovica Prison was built during the Austro-Hungarian rule and has served as prison ever since. From November 18 1991 until August 14 1992, one quarter of it served as a prison camp for prisoners from Croatia. Sulejman Tihić, Bosniak and a former member of the Presidency of Bosnia and Herzegovina testified about this. His testimony shows that not only prisoners from Croatia, but also those from Bosnia and Herzegovina were held at the camp.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]Soon after the fall of Vukovar, a number of civilians, patients and doctors from the Vukovar hospital were brought to Sremska Mitrovica.[footnote]ICTY Trial Chamber judgment in the trial of Mrkšić at al. (Radić and Šljivančanin) of 27 September 2007, ICTY website, paragraph 213[/footnote]

According to the article “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s” by Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, the main building of the Prison, which was around sixth meters long and eight meters wide, was used to house the prisoners from Vukovar and those from Bosnia and Herzegovina, while the torture was done in the basement.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016 [/footnote]At first, the prisoners did not have the possibility of washing up and because of lice infestation were sprayed with an insecticide. Only a couple of months later, that is, after the arrival of the Red Cross, they washed themselves for the first time.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]The prisoners were beaten during their ride to Sremska Mitrovica, i.e. in Bogojevo where the bus would stop, then at the entry to the Sremska Mitrovica Prison, where they had to walk through the gauntlet of soldiers, and then they were tortured on a daily basis during the whole time of their imprisonment.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016 [/footnote]Besides the guards, the interrogators in Sremska Mitrovica used brutal methods as well. Prisoner Šandor Željko stated that certain Šalić, member of the Counterintelligence Service (KOS), forced him to eat salt and pepper during interrogation, after which he had stomach pains and sores in his mouth.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016 [/footnote]

The camp in Niš was situated in the building of the Penitentiary and Correctional Institution. It was opened on November 18 1991 and operated until February 26 1992. The commander of the prison camp in Niš was a certain Colonel Jovanović, whose first name could not be found neither by the authors of the article “Prison camps in Serbia in the 1990s” nor BIRN journalists.[footnote]Barbara Matejčić and Zoran Kosanović, “Revealed: Vukovar Croats Were Tortured in Niš”, BIRN, 27 January 2011[/footnote]

The interrogators in Niš were trying to extract confessions from the prisoners by playing good cop-bad cop, whereby two police officers would first beat the prisoner and then the third one would come to talk him into signing the confession, promising that the torture would stop that way.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]

Some former prisoners state that the camp in Niš was the worst. Niko Mirosavljević says: “All the camps were nasty, but Begejci and Niš were the worst. We were beaten all the time in Niš. They would storm the rooms day and night and beat people even in bed. They beat us both with batons and rifle butts.”[footnote]Barbara Matejčić and Zoran Kosanović, “Revealed: Vukovar Croats Were Tortured in Niš”, BIRN, 27 January 2011[/footnote]Petar Mesić died of the beatings at the camp and in 2010 his remains were exhumed at the city cemetery in Niš together with another nine unidentified persons.[footnote]“Ekshumirano deset tela”, Danas, 28 January 2011[/footnote]Branimir Kosec, Croatian priest and a prisoner, also testified of the murder, i.e. circumstances of Petar Mesić’s burial, as Colonel Jovanović requested him to perform the funeral.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]

The places of imprisonment in Belgrade were located on the premises of Military Investigative Prison (VIZ) at the Military Court in 29 Ustanička Street, and in Banjica, in the building of the Security Institute, in the vicinity of the Military Medical Academy. Both places were operational from October 1991 until August 14 1992.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]

The Military Investigative Prison consisted of various detention rooms, cells, solitary confinements and interrogation rooms. Prisoners from Croatia were housed in a secluded wing where it was not possible to see other prisoners through the window.[footnote]Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps: http://hdlskl.hr/svjedocanstva/viz-beograd/[/footnote]The Military Prosecutor’s Office was also in the building of the Military Court in Ustanička Street. This Prosecutor’s Office raised charges against Vlado Ošust and five other prisoners from the Military Investigative Prison for armed rebellion and the Military Court rendered a first-instance judgment in April 1992, sentencing them to imprisonment of nine to 13 years. Ošust says that “a number of Croatian soldiers and police officers, some 123 of them, were imprisoned at the Military Court in Belgrade, where they were put on trial”.[footnote]“Čvrsto smo vjerovali da će i taj dan doći, dan naše slobode”, 24 sata, 14 August 2017[/footnote]

Aside from the ones mentioned, there were several other prison camps for Croats. They were located in the barracks of the Yugoslav People’s Army in Zrenjanin, in the Military Prison in Šid and in the Military Prison in Aleksinac.[footnote]HLC Dossier: Crimes against Croats in Vojvodina, Humanitarian Law Centre, Belgrade, 2019, p. 47[/footnote]The Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps state that the camps also existed in Novi Sad, specifically in the SPENS Centre, in Bubanj Potok and in Sombor.[footnote]Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps[/footnote]Besides Croatian citizens from Vukovar and its surroundings, a certain number of Serbian citizens of Croatian ethnicity who lived in Vojvodina were also imprisoned at the prison camps in Serbia. In addition to the case of Mladen Lončar from Ilok, the Humanitarian Law Centre (HLC) also documented the case of torture of Ljubomir Kuraj from Beška, who had spent six months at the camp in Sremska Mitrovica and subsequently testified about the torture by JNA members, and the case of torture of Ivan Paradžiković from Kukujevci, who spent a total of 79 days in different camps in Serbia, where he was beaten regularly.[footnote]HLC Dossier: Crimes against Croats in Vojvodina, Humanitarian Law Centre, Belgrade, 2019, p. 47-48[/footnote]

The camps for Croats in Serbia were dissolved after the exchange of prisoners on August 14 1992, as a result of political agreement between Serbia and Croatia. At the meeting of the Prime Minister of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (FRY) Milan Panić and Croatian Prime Minister Franjo Gregurić in Geneva on July 29 1992, it was agreed to make an “all for all” exchange.[footnote]“Čvrsto smo vjerovali da će i taj dan doći, dan naše slobode”, 24 sata, 14 August 2017[/footnote]The exchange took place in Nemetin, a hamlet near Osijek, when 714 Croatian prisoners were released. Although the prisoners were made to believe until the last moment that the exchange might not happen, it actually occurred and was later celebrated in Osijek.[footnote]“Čvrsto smo vjerovali da će i taj dan doći, dan naše slobode”, 24 sata, 14 August 2017[/footnote]

“Twenty corpulent military police officers, well equipped with batons, sticks, iron bars, iron knucklers etc. were waiting for us. Later we found out that they were specially trained for such occasions in Bubanj Potok near Belgrade, where the military police base is stationed. They did not wait for us to be lined up and examined, but started beating about fifty of us from the bus right away and we were not allowed to shout or scream. They were only shouting at us to put our heads down and our hands behind our backs”, A.B. about the arrival to the camp in Begejci.[footnote]Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps[/footnote]

“We were freezing because the room did not have an attic, it was just covered with tiles. We were given food twice a day, a slice of bread, some tea and a bit of salami, sausage or a small pâté tin for the three of us. In addition to torturing us by starvation, they also exercised psychological torture over us, prisoners. We had to sing Serbian songs which we did not know and they would beat us for that. At night they would come to us with dogs, drunk, and enjoyed sadistically in brutally thrashing us. I didn’t think I would survive”, H.A. about the conditions in the Stajićevo camp.[footnote]Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps [/footnote]

“Individual interrogations are beginning, aimed at raising charges for armed rebellion and the commission of ‘war crimes’. Any military action of Croatian soldiers and police officers against enemy’s live force and material and technical resources is considered to be an offence or even a crime. Various methods of physical and psychological coercion – extortion were used in the interrogation processes. The treatment of prisoners by some guards was inhumane. Basic rights of prisoners were often violated. Two prisoners died of injuries and many have lasting consequences”, Vlado Ošust about his captivity in the Sremska Mitrovica Prison.[footnote]“Čvrsto smo vjerovali da će i taj dan doći, dan naše slobode”, 24 sata, 14 August 2017[/footnote]

“The interrogators here also wanted to extract confessions for alleged wrongdoings which had never been committed. If you did not confess, you would usually be sent to the so-called cooling. You would be usually taken to a cooling by a non-commissioned officer and two police officers, to the so-called catacombs of Niš (basement solitary confinement), they would stripped us naked and barefoot and lock us in a 2×1.5 meter room with bars on windows without window glass, and outside was snowing, minus 20°C, V.M. on torture methods in Niš.[footnote]Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps[/footnote]

“As far as my stay in Belgrade is concerned, the most difficult part was to endure psychological torture. Since there were several accused, I was supposed to be put on trial only in the last group. However, I was not present at the trial, because the exchange had happened before. It was awful constantly anticipating if there would be a trial, who would come from Vukovar and accuse me and what lies would be told. Still, before it happened, there was the exchange. In Nemetin I saw a ‘friend’ Simić in the uniform of the militia of ‘Krajina’. The very trip from Belgrade to Nemetin was at the verge of death. We were stopping in villages in Baranja and the civilians would enter the bus, beat us and curse us, while UNPROFOR was only watching”, R.A. about the exchange of prisoners in Nemetin.[footnote]Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps [/footnote]

Slobodan Milošević[footnote]Slobodan Milošević, Second Amended Indictment, ICTY, 23 October 2002 [/footnote]and Goran Hadžić[footnote]Goran Hadžić, Second Amended Indictment, ICTY, 22 March 2012 [/footnote]were charged before ICTY. However, these court cases were ended because both the accused died. As it is stated in the indictment against Slobodan Milošević, who was the President of Serbia and a member of collective presidency of the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia at the time of prisoners’ captivity, he, as well as Hadžić, was charged with participating in criminal enterprise in which a regime of persecution was established, including, among other crimes, a prolonged and routine imprisonment and confinement, torture and inhuman living conditions for several thousands of Croatian and other non-Serbian civilians in detention facilities within and outside Croatia, including prison camps located in Montenegro, Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.[footnote]Slobodan Milošević, Initial Indictment for Croatia, ICTY, 27 September 2001[/footnote]

Goran Hadžić was the Prime Minister of the self-proclaimed Serbian Autonomous Area of Slavonija, Baranja and Western Syrmia (SAO SBZS) and then the president of the Republic of Srpska Krajina (RSK), Croatia. He was only arrested in 2011, after decades in hiding. The crimes he was charged with include unlawful confinement or imprisonment under inhumane conditions of Croats and other non-Serbians in several detention facilities in Serbia: the Stajićevo agricultural estate, barracks in Zrenjanin and Sremska Mitrovica and several facilities in Croatia, including the Velepromet (near Vukovar) and the Territorial Defence Training Centre in Erdut.[footnote]Goran Hadžić, Second Amended Indictment, ICTY, 22 March 2012[/footnote]

In the case Mrkšić et al. before ICTY[footnote]ICTY Trial Chamber judgment in the trial of Mrkšić et al., 27 September 2007[/footnote], the presence of camps for Croats on the territory of Serbia was confirmed in the first-instance judgment. Witnesses, such as General Aleksandar Vasiljević and Colonel Bogdan Vujić, were minimising their role, putting the blame on army members who died or those already accused for other crimes.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]

In 2006 , the War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office (TRZ) in Belgrade, in co-operation with Croatian State Attorney’s Office, started an investigation of camps in Serbia.[footnote]Tatjana Tagirov, “Ratni zločini: Čovek sa velikim Č”, Vreme, 29 May 2008 https://www.vreme.com/cms/view.php?id=635882[/footnote]In the same year, HLC filed a compensation claim to the First Municipal Court in Belgrade on behalf of 19 women and minors who had been held in the camps in Begejci and Sremska Mitrovica.[footnote]Charges against Serbia for the imprisonment of Croatian civilians in prison camps on the territory of Vojvodina after the fall of Vukovar in 1991 (Serbian only), Humanitarian Law Centre, 17 October 2007 [/footnote]One year later, HLC filed charges to the same court on behalf of 12 former prisoners for their imprisonment in the camps in Begejci, Stajićevo and Sremska Mitrovica, but the charges were dismissed by the first-instance judgment. Upon HLC’s appeal the case went to the Court of Appeal and it is still pending.[footnote]Dušan Komarčević, “Tužba hrvatskog logoraša pred sudom u Beogradu”, Radio Slobodna Evropa, 14 November 2018 [/footnote]

In 2008, Prisoners’ Association Vukovar 1991, in co-operation with HLC, filed criminal charges to the War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office against NN persons from several prison camps in Serbia, accusing them of war crimes against the prisoners of war. Preliminary criminal investigation is underway: the Prosecutor’s Office is awaiting information from the police, while the army is silent.[footnote]Barbara Matejčić and Zoran Kosanović, “Revealed: Vukovar Croats Were Tortured in Niš”, BIRN, 27 January 2011[/footnote]

Marko Crevar, a guard, earlier member of the Territorial Defence and militia of the Republic of Srpska Krajina, was accused of violence against prisoners in Sremska Mitrovica. In 2015, Crevar was convicted by the War Crimes Department of the Higher Court in Belgrade and sentenced to one year and six months’ imprisonment for torturing prisoners of war during interrogation and inflicting bodily injuries.[footnote]Higher Court in Belgrade judgment against Marko Crevar in the Sremska Mitrovica case (Serbian only), 18 February 2015[/footnote]

Prisoners mention various nicknames of the guards in their testimonies; the nicknames which repeat in several camps show that after the closing down of one camp the same guards were transferred to the next one, where they continued torturing prisoners.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]The camp guards are still hiding behind the nicknames and incomplete names, such as Šeki, Rambo, Tyson… It can be assumed that the very purpose of those nicknames was to hide the guards’ identities and make their prosecution impossible.

In 2018, the County Court in Osijek began a trial in absentia against General Aleksandar Vasiljević, the chief of the JNA Security Service of the Federal Secretariat for People’s Defence (SSNO) for crimes against Croats in the camps in Serbia, where five persons were killed in the camps of Begejci and Stajićevo, seven in the camp in Sremska Mitrovica and one in Niš. The indictment also included Colonel Miroslav Živanović who passed away in the meantime.[footnote]“U Osijeku počelo suđenje bivšem šefu KOS-a Aleksandru Vasiljeviću za ratni zločin”, Večernje novosti, 22 October 2018[/footnote]

A group of former prisoners sued Serbia to the Civil Court in Zagreb in 2019 for unlawful detention and violation of the Geneva Conventions. In charges against Serbia, former prisoners make reference to the fact that they were registered by the ICRC, that they possess necessary medical documentation, as well as to the fact that Montenegro has compensated prisoners from its territory. Besides them, some 50 prisoners are suing Serbia before Serbian courts.[footnote]“Logoraši iz Hrvatske tuže Srbiju: Za svaki dan u logoru traže po 135 evra, plus povrede”, B92, 15 June 2019 [/footnote]

In March 2020, the Government of Croatia promised financial and professional assistance to 5000 prisoners who were suing Serbia and who, as reported by the Croatian Association of Prisoners in Serbian Concentration Camps, are ready, after they exhaust all legal remedies, to seek justice before the European Court for Human Rights.[footnote]Enis Zebić, “U planu pet tisuća tužbi hrvatskih logoraša protiv Srbije”, Radio Slobodna Evropa, 6 March 2020[/footnote]

According to the statement of Đorđe Kitaresku, who had access to the camp because he knew the terrain and who had talked about the torture in the camp, the camp’s building in Begejci was demolished and the remaining material was used to build a church in the village of Višnjićevo.[footnote]Tatjana Tabački and Andrej Jakovljev, “Prison camps in Serbia in the 90s”, YU Historija, 2016[/footnote]In 2001, the name of the village was also changed and Begejci is now called Torak in order to be linked as little as possible to the crimes committed in the village during the conflict of the 1990s. Prison camp in Stajićevo is not marked, either.

The associations of prisoners who were imprisoned in Begejci and Stajićevo have been trying since 2009 to mark these places with memorials and commemorations, but they have not fully succeed to date. In 2009, their arrival and the commemoration that was planned were cancelled because of the opposition of the Association of War Invalids from Zrenjanin, who protested against the placing of a memorial plaque with hunger strike and by organising round-the-clock watch to make sure that the memorial was not placed.[footnote]Miroslava Pudar, “Obeležiti ‘logore’ za Hrvate na godišnjicu pada Vukovara”, Danas, 18 October 2011[/footnote]They opted for such a move after the president of the Zrenjanin Assembly, Aleksandar Marton, member of the League of Social Democrats of Vojvodina, met with a delegation of lawyers of the Association Vukovar 1991 and, on behalf of the local self-government, promised that the memorial plaque would be placed in Stajićevo and Begejci.[footnote]“Zrenjanin: Vojni invalidi traže smenu”, Večernje novosti, 26 September 2009[/footnote]The Interior Ministry first postponed and then banned the arrival of former prisoners.

For years following this ban, prisoners’ associations had been announcing the placement of the memorial plaque in Stajićevo, but no progress was made until 2016. That year, Aleksandar Vučić, then Serbian Prime Minister, met with the prisoners’ delegation and promised that the commemoration in Stajićevo would be allowed.[footnote]“Prvi srbijanski dužnosnik primio vukovarske logoraše i branitelje”, Večernji list, 12 July 2016[/footnote]This meeting resulted from an agreement between Serbia and Croatia on solving open issues, known as the Declaration of Subotica, signed on June 20 2016 in Subotica by the Prime Minister of the Government of Serbia Aleksandar Vučić and President of the Republic of Croatia, Kolinda Grabar-Kitarović.[footnote]“Vučić i Grabar-Kitarović potpisali Deklaraciju o unapređenju odnosa između Srbije i Hrvatske”, Portal Subotica.com, 20 June 2016 [/footnote]

One year later, in 2017, after the meeting with Aleksandar Vučić at the Summit of the Southeast Europe Cooperation Process (SEECP), President Grabar-Kitarović said that a visit of former prisoners to Stajićevo had been agreed for the autumn, where they should place wreaths “in peace and dignity”.[footnote]Dalibor Stupar, “O logorima za Hrvate i Bošnjake u Srbiji tokom devedesetih”, VOICE, 4 July 2017[/footnote]

However, once again, the commemoration did not happen. President of the Association Vukovar 1991 Zoran Šogut said that former prisoners attempted twice to place memorial plaque in Stajićevo, but were rejected by the state leadership[footnote]Barbara Matejčić and Zoran Kosanović, “Revealed: Vukovar Croats Were Tortured in Niš”, BIRN, 27 January 2011[/footnote], while Branko Borković, a commander of the defence of Vukovar, thinks that marking of the places of captivity must be a precondition for Serbia’s accession to the European Union.[footnote]“Čvrsto smo vjerovali da će i taj dan doći, dan naše slobode”, 24 sata, 14 August 2017 [/footnote]Non-governmental organisations, such as Women in Black, are calling on local authorities to place the memorials[footnote]Miroslava Pudar, “Obeležiti „logore“ za Hrvate na godišnjicu pada Vukovara”, Danas, 18 October 2011[/footnote]because only by admitting to the war crimes would lead to dealing with the past and ultimately to reconciliation.

In August 2018, Serbian President Aleksandar Vučić, talking about the points of the Declaration of Subotica that had been implemented, said that it was agreed to start talks with regard to the marking of the places of suffering of Croats in Serbia during the 1990s and that their proposal was being awaited for in order to do it.[footnote]“Šta je sve Srbija učinila za ‘svoje’ Hrvate”, RTS, 8 August 2018[/footnote] However, by April 2020 there has been no information that any agreement was made.