The outcome of the armed conflict in the former SFR Yugoslavia, between 1991 do 2001, is the violent death of 130 000 persons. Over 10 000 are still classified as missing. Serbia’s officials and institutions have, from the beginning of the armed conflict to this day, with very few exceptions, denied the involvement of the SFR and Serbian armed forces in the conflicts in Croatia and Bosnia and Herzegovina. They have also denied the existence of any war crimes on the territory of Serbia in relation to these armed conflicts.

As an antithesis to the practice of forgetting the atrocities of war, the platform ratusrbiji.rs strives to inform and educate about the existence of secret mass graves, concentration camps and torture, murders and persecution of minorities, forced mobilization, paramilitary units’ crimes, as well as the human rights breaches in the Presevo valley between 1991 to 2001. The platform does this through connecting court-determined facts, official data of state and international institutions, testimonies of witnesses, survivors and victims’ families, as well as public information gathered by civil society organizations in Serbia.

The platform ratusrbiji.rs was supported by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany. The content and opinions featured on the ratusrbiji.rs website are those of the Youth Initiative for Human Rights, and may not reflect the official stance of the Ministry for Foreign Affairs of the Federal Republic of Germany.

Several years after the prison camps for Croats were closed, at the height of war in Bosnia, on the territory Serbia, prison camps were opened for Bosniaks. After the fall of Srebrenica, that is, the murder of more than 7000 men and forcible transfer of women and children in July 1995, the Army of the Republic of Srpska (VRS) headed towards the other UN protected zone – Žepa.1After the Krivaja 95 operation, that is, the attack on the Srebrenica region, Ratko Mladić, chief of the General Staff of the Republic of Srpska Army (1992-1996) ordered the Stupčanica 95 operation, aimed to “liquidate the enclave” of Žepa. Ratko Mladić and Hamdija Torlak, President of the Executive Board and member of the War Presidency of Žepa met in late July 1995, when Mladić requested disarmament and promised the evacuation of civilians. After the meeting, the civilians started evacuating towards Kladanj. The evacuation in the Tolimir trial before ICTY was characterised as forcible transfer, which is a crime against humanity.2

Since men from the Žepa region were already aware of what had happened in Srebrenica, they decided to cross the Drina River to avoid the Republic of Srpska Army and to surrender to FRY authorities. The men who decided to cross over to the territory of Serbia on makeshift rafts, with the idea that in this way they would obtain refugee status more easily and go to third countries, were mostly members of the Army of Bosnia and Herzegovina, but there were also civilians and minors among them.3

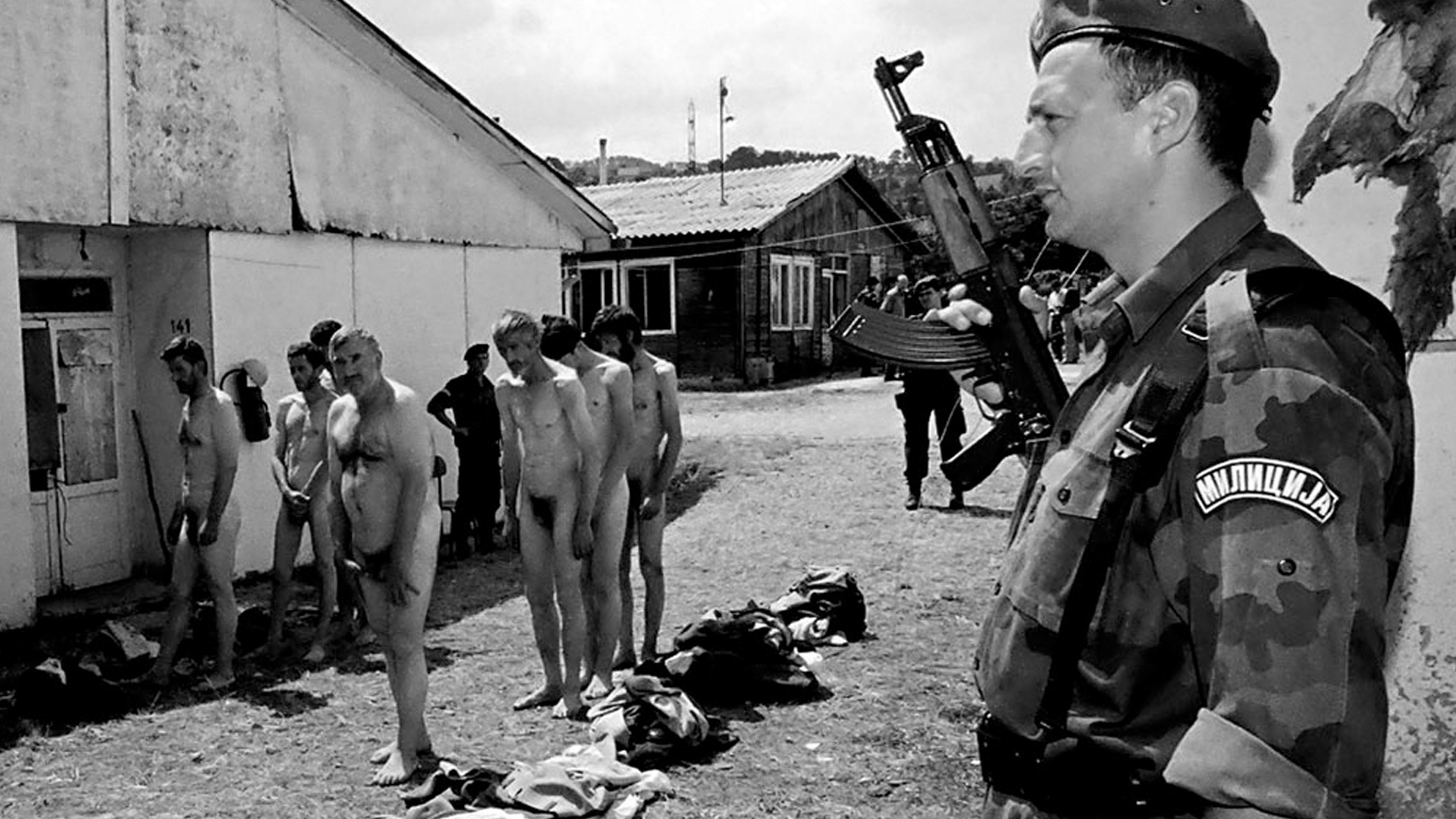

When they crossed the river, they were awaited by the border battalions of the Yugoslav Army (VJ) and members of the Police Special Units (PJP).4

A group that crossed the Drina River on August 1 and then climbed up Zvijezda Mountain was met by the members of Yugoslav Army’s 16th Border Battalion, who took them to the village of Jagoštica (Bajina Bašta municipality), where the headquarters of this battalion was located. There, they were met by the members of Užice Police Department (SUP Užice) and locals.5

A group that swam across the border on August 4 or 5 was taken to Bajina Bašta police station (OUP Bajina Bašta).6The Humanitarian Law Centre (HLC) in its Dossier Šljivovica and Mitrovo Polje estimates that around 800 Bosniaks from the Žepa region entered Serbia in the period between July 31 and October 25.7

Having entered Serbia and met with the members of the army and the police, the men were registered, searched and interrogated. During the interrogation, which mostly concerned their roles in the BH Army, the prisoners were beaten and cursed at.8 In addition to physical torture which began at the very entry into Serbia, they were also intimidated by threating that they would be taken to Višegrad and handed over to Milan Lukić, the commander of paramilitary unit Avengers, whose members are responsible for the abductions and murders of Yugoslav citizens in Sjeverin and Štrpci and convicted for crimes against non-Serbian population in Višegrad, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Instead, the prisoners were loaded onto the trucks with tarpaulin covers and transported to the Šljivovica camp. During the ride, some prisoners were suffocating from the lack of oxygen and the police responded with sticks to their attempts to get fresh air.9

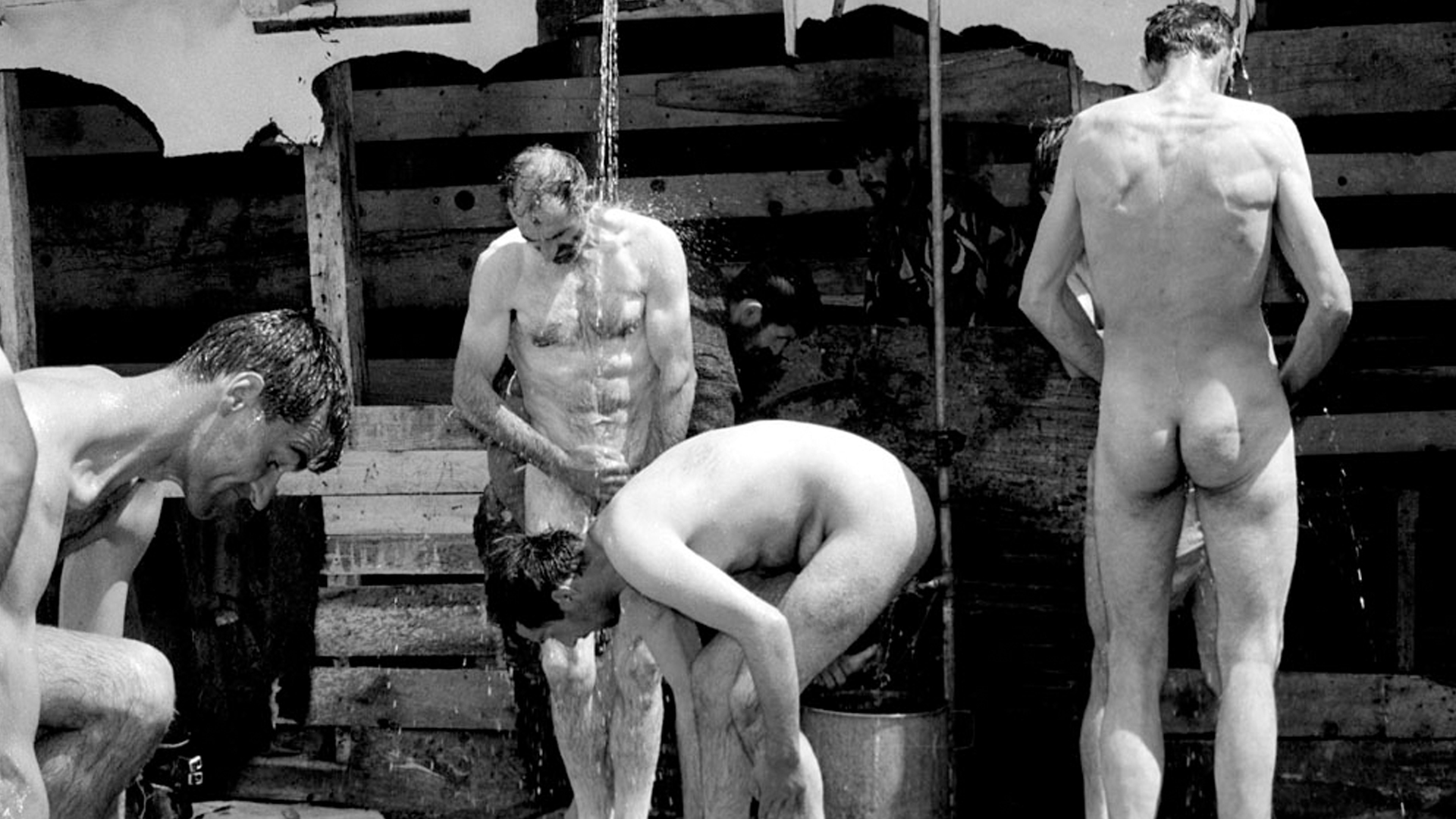

The Šljivovica camp is located in the eponymous village of Šljivovica near Užice. It is estimated that around 350 prisoners were housed there.10The camp was secured by the police officers from the Užice Police Department, while the inspectors from the Border Affairs, Aliens, Travel Documents and Weapons Division interrogated the prisoners. The main interrogator was the Head of the Division Radisav Ojdanić. The camp consisted of abandoned barracks which belonged to the Planum construction company, with the camp management housed in one and the prisoners in the other barrack.11Upon their arrival to Šljivovica, the prisoners had to walk down the gauntlet of soldiers and then doused with cold water and forced to kneel on concrete.

Since the Šljivovica camp was not big enough to receive all prisoners, having walked through another gauntlet, some of them were put in buses (Raketa Transport Company) and transferred to a camp in Mitrovo Polje the very next day. The Mitrovo Polje camp was located near Aleksandrovac; it was opened on August 4 1995 and closed on February 9 1996. It consisted of two buildings – Rasina and Sutjeska.12The guards were police officers from the Kruševac Police Department (SUP Kruševac) and the main interrogator was Vladimir Milićević, head of the Border Affairs, Aliens, Travel Documents and Weapons Division of the Kruševac Police Department.13

There were no beds in rooms in which the prisoners in the Šljivovica camp were housed; they had to lie on a concrete floor and only a few prisoners were given blankets.14The prisoners of Mitrovo Polje, whose number is estimated at 450, were sleeping in small beds for children or on the floor.15For the first few months the prisoners were not allowed to wash themselves or take care of hygiene at both camps and consequently they got lice. The food was irregular and scarce and it worsened over time. When there was food, it had to be eaten quickly in order to avoid beatings, which also meant that not all the prisoners had their turn to eat.16In Mitrovo Polje, the prisoners were allowed to pick herbs and use it to make tea.17

The camps had latrines and in order to use them, the prisoners had to ask permission from the guards, to make the sign of the cross and say their Serbian name given to them by the guards which they were forced to respond to.18Since they were beaten and abused every day, even during the night or when they went to the toilet, the prisoners were avoiding contacts with the guards and were relieving themselves in their rooms.

In addition to physical abuse, the prisoners were forced to fight each other, to make the sign of the cross make the sign of the cross in an Orthodox manner and sing Chetnik songs.19Police officers who served as guards called them names, making fun of their skinny and neglected appearance. They were singing: “You are undernourished Alija because you are a Balija20” (Neuhranjen si, Alija, zato što si Balija)21 and called the prisoners “artists”; they also forced them to walk with their heads down, thus exercising their power over the prisoners. Some of the torturing methods included forcing the prisoners to stare directly at the sun until they faint, the threats of murder by putting a rifle barrel into prisoners’ mouth although the barrel was actually empty,22giving the prisoners a jar of pickled hot peppers after several days of starvation.23The prisoners were threatened with being returned to Bosnia and handed over to Radovan Karadžić, President of the Republic of Srpska, now convicted for genocide and crimes against humanity in BH.24The staff of the hospital in Užice was providing medical assistance to the prisoners in Šljivovica, but the prisoners later testified that the doctors were often hostile.25One prisoner in Šljivovica died of a bowel obstruction, although adequate reaction of medical staff could have prevented that.26

Although it is difficult to talk about sexual violence in patriarchal communities, especially sexual violence against men, several prisoners from Šljivovica and Mitrovo Polje reported to HLC researchers what was happening at the camps, although it is assumed that there were many more victims of sexual violence. Regarding the brutality of one of the guards, A2 says: “He forced us to have sex with one another, to touch one another, to ejaculate in one another’s mouths. He and some other policemen urinated on us.27”In addition to rapes and urination on the prisoners, once the guards put a water hose in a prisoner’s anus and then turned on the tap at high water pressure.28

The camps for Bosniaks were visited by several international organisations. The first one to visit the camps for Bosniaks in Serbia is the International Committee of Red Cross (ICRC). Although they were not allowed to get in at first, ICRC representatives still managed to enter the camp in Mitrovo Polje on August 4 and then in Šljivovica on August 18 1995. ICRC registered almost all prisoners except for those held in the so-called “isolation” who were reached only a couple of months later. The prisoners who were in solitary confinement were interrogated about their links with the BH Army in particular.29Although hygienic conditions at the camps improved after the arrival of ICRC (hygiene, bed linen)30, Amir Omerspahić, one of the former prisoners at Šljivovica said that he would have preferred that the Red Cross representatives had stopped coming as after their visits the guards would treat the prisoners even worse. ICRC was bringing food and clothes to the camp31, but according to the prisoners it was never given to them.32

In October 1995, the camps were also visited by the Expert Team of FRY Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The Team gave recommendations for the improvement of conditions at the camps (food, hot water), but failed to record anything about the abuse of prisoners which the survivors testify of, although the level of torture at the camps decreased after this visit.33

In April 1996, the BH Federal Commission for Missing Persons entered Šljivovica and ascertained that this was a closed-type camp surrounded with barbed wire fence and guarded by trained dogs and that the prisoners in there were in a very bad state. The BH Commission found relatively small number of prisoners at the camps (276 out of 799), as the majority had been sent to third countries earlier.34

When the camp in Mitrovo Polje was closed, the remaining prisoners, 194 of them, were re-transferred to Šljivovica, where they stayed until the camp was closed on April 10 1996.35 On the day the camp was closed, 13 or 14 prisoners were held under suspicion of war crimes, which caused negative reaction of BH authorities and UNCHR, after which the prisoners were released.36

The time spent at the camp has left lasting consequences on the prisoners. Some are physical, caused by frequent beating and unhygienic living conditions, while others are mental, such as depression and PTSD, developed as a result of living in inhumane conditions and permanent fear. The prisoners who sought psychological support now cope more or less successfully with what they were through and talk about their experiences, although it took them years to get empowered and speak up.

“Upon arrival they started beating us right away, they were even making fun of us; they told me to fix my hair because the Red Cross was recording us. My father and I had spent six months in room number 6. The hardest moments at the camp were starvation because in the six months we were never full. I was never allowed to raise my head”, Emir Agić, who had to present himself as Slaviša at the camp.37

“I had a cut on my thumb and when those special units came to take me, and they took us near the village of Jagoštica, I didn’t know the area then. I was constantly beaten then by one man and since my hands were on the back of my neck and my head down, they broke my fingers. My fingers broke, I started bleeding severely and I was in pain, but I couldn’t move my hands from behind my neck. They brought us to that village of Jagoštica, there were already 92 of us in the group, and forced us into a tarped truck. It was very hot and at dusk they drove us to that village of Šljivovica, I didn’t know that area, too, where we were taken by those from the Serbian Interior Ministry. I was thinking, everything would be great now because we got rid of the army, however, it’s only then that the true chaos and hell began. Every night interrogations, writing statements, accusations for something that never happened, I was practically a child at the time, it was horrible. My hand was deteriorating more and more every day. One day some paramedics from Užice came, I applied to be checked out and the doctor said that I had to go to the hospital urgently. The next night I went to Užice in a police car and I felt relieved for the first time, because the doctor there was so kind, I will never forget it, first he saved my life and then he saved my hand”, Amir Omerspahić, prisoner from Šljivovica.38

“They formed isolation rooms in which certain people were placed, those marked as some kind of war criminals, they were particularly tortured, starved. The beatings were such that one couldn’t easily notice that you were beaten; for example, they would beat you on your feet, you would sit in a chair, on your knees, and then they would beat you on your feet or on your kidneys”, Senad Jusufbegović, prisoner from Mitrovo Polje.39

The facts that men from Žepa were met upon their crossing the border by the Police Special Units (PJP) and Yugoslav Army’s border battalions, as well as by local police stations and police departments, speak of the involvement of the highest government structures of Serbia and the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. Former European Union’s Special Envoy to the Former Yugoslavia Carl Bildt testifies that President Slobodan Milošević was informed about the situation around Žepa and that taking the men from that enclave instead of catching them and handing them over to the Army of the Republic of Srpska, was a political, opportunistic choice until August 1995.40 Finally, the existence of the camps was proven by the forming of the Expert Team of FRY Ministry of Foreign Affairs, which denied torture, but found that prisoners were not treated in accordance with the law.[41

Radisav Ojdanić and Vladimir Milićević, chief interrogators at the camps of Šljivovica and Mitrovo Polje, are both retired today. Ojdanić and Milićević were not responsible for the security of the camp, as this was done by the heads of the police divisions in Užice (Šljivovica) and Kruševac (Mitrovo Polje).

Ljubiša Diković, the general who was in 1995 the commander of the Yugoslav Army’s 16th Border Battalion, which was catching men who tried to find refuge from the Republic of Srpska Army in Serbia and taking them to the camps was appointed Chief of the General Staff in 2011 and retired in 2018.42

In the Milošević trial before ICTY, Obrad Stevanović, commander of the Police Special Units (PJP) in 199543, testified of taking around eight hundred captured Bosniaks to the camps in Šljivovica and Mitrovo Polje, for whom he stated that they were members of BH Army.44

Today, Stevanović is a full professor at the University for Criminal Investigation and Police Studies in Belgrade.45Obrad Stevanovic was never persecuted.

Responsibility for the camps of Šljivovica and Mitrovo Polje was not being established in court proceedings before ICTY, although evidence of their existence were presented in the cases of Milošević, Tolimir, Popović, Perišić and Stanišić and Simatović.46

The camps for Bosniaks in Serbia were also not mentioned in the judgment in the case of Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Yugoslavia for the genocide committed on the territory of BH, conducted before the International Court of Justice from 1993 until 2007.47

In 2011, HLC filed a criminal complaint against several identified and unidentified persons who were committing violence at the camps during the 1990s to the War Crimes Prosecutor’s Office (TRZ). TRZ found that there was no war crime against the prisoners of war or crime against humanity48 , i.e. the crime introduced into national legislation in 2006. For that reason TRZ did not consider the prosecution of crimes against humanity because at the time of the offence it was not criminalized in national laws.49

HLC then addressed the Constitutional Court which rejected the appeal. In 2014, HLC submitted two applications against the Republic of Serbia to the European Court for Human Rights on behalf of former prisoners and families of prisoners who did not survive. The ECtHR rejected them, finding that the applications were too late and that they should have been submitted within the period of six months after finding out that TRZ would not prosecute the crimes.50

In the period of 2007-2008, HLC was also initiating compensation proceedings on behalf of former prisoners. For example, in the case Enes Bogilović et al, the First Basic Court rendered a decision in 2010 rejecting Claimants’ claim as unfounded. The Court of Appeal quashed this decision in 2012 and ordered a re-trial because it found that during the proceedings the court took into consideration the evidence presented by only one side. After that, the First Basic Court once again ruled to reject the claims and in 2014 the Court of Appeal confirmed this judgment.51

It was similar with other cases, such as the case of Omer Čavčić et al.52 Mujo Vatreš, who spent more than six months at the camps in Serbia and lost around 50kg won the case and compensation of RSD 500.000 in 2013. This is the first judgment in favour of a former prisoner and it is also important because it confirms that the prison camps existed and that the Republic of Serbia is responsible.53

The places of suffering of the prisoners from Bosnia and Herzegovina are not marked. The barracks in Šljivovica were burned down in order to obliterate the memory of them, and the remaining two are deteriorating year after year. It is only awaited for them to quietly and finally collapse and that we completely forget that people were ever raped there. Today, the Training Centre of the Ministry of the Interior of the Republic of Serbia stands at the place where the camp in Mitrovo Polje once was. At the Training Centre, there are classrooms and indoor and outdoor sports facilities, and it offers several types of training, including “camping”.54

Apart from the absence of material memorialisation, there is almost no word in public about former prison camps. When you search for words Šljivovica and Mitrovo Polje on the internet, they are mentioned as tourist attractions, attractive for the beauty of surrounding nature, while only the survivors and civil society organisations talk about the camps for Bosniaks in Serbia.55